In April, Alex joined a trip to Rwanda and Burundi, organised by Omwani, a York-based green coffee importer, in partnership with Rwandan coffee farm Rwamatamu and Burundian washing station, Migoti.

Learning more about coffee farming and processing, the challenges faced by growers and the opportunities to support the industry, has always been hugely important to us. As far as we are concerned, coffee growers and importers are our colleagues. None of our businesses could survive without the other. Support of and open communication with each other, is critical for our industry as a whole.

When the opportunity to join this trip came up, we jumped at the chance. We really want to visit coffee growing regions as a family but thought Alex going alone for the first one was probably a good idea! He’s come back even more eager to take the kids along next time.

Terminology & general information

Washing Station or Wet Mill - facilities where local farmers, usually smallholders, bring their coffee cherries. Here each farmer’s crop is ‘floated’ (so un-ripe cherries can be picked out) weighed and priced. They are paid for floaters but at a much lower rate. Local smallholders deliver the day’s crop as soon as possible after the cherries have been picked. They arrive all night long and washing station staff work throughout the night sorting and preparing cherries for processing.

Processing - how the coffee cherry is removed from the fruit. There are various processing methods, each of which has an impact on the end result, the two main methods are washed and natural. Processing happens at the washing station before coffee is transferred to a dry mill. Some farms have a washing station on site or cooperatives/other groups establish washing stations and dry mills that local smallholders bring their crops to.

Dry Mill - facility where processed coffee beans go through a final sorting and grading process before being prepared for sale.

Smallholding - family owned and operated farms producing such small amounts of coffee that they cannot sell direct to importers. In African coffee-producing regions these farms are usually organic because pesticides and non-natural fertilisers are not widely available. Washing stations/wet mills are established in remote regions so growers can bring their crops to be processed as quickly as possible. In picking season they’ll spend perhaps eight hours picking ripe cherry by hand (they ripen at different times even on the same branch) then walk 5-10kms carrying the day’s crop to the washing station.

Before your visit, did you have any preconceptions about coffee farming in Rwanda and Burundi?

Not particularly. I have visited coffee farms and washing stations before, so have a good idea of what happens, the equipment used etc. However I hadn’t been to either Rwanda or Burundi before and I knew that all the regions we were visiting are pretty remote so had no idea if what I’d seen before would be typical of coffee growing in these areas.

Can you describe a typical day on the trip?

In Rwanda, we’d get up early, have breakfast then get straight into cars as everywhere we visited was at least two hours away. There were 12 of us in total so we separated into groups and were accompanied by a local person who translated for us and told us about the area.

We’d have plenty of time at the farm or washing station, observing how things worked and chatting with the staff there. Wherever possible we cupped the new season coffees that are sample roasted on site. It was pretty early in the picking season so there wasn’t a huge amount to try. We’d head back to our accommodation in the afternoon and have dinner together. It was lovely to try local dishes, such as goat stew served with flat bread.

We got the chance to visit a teaching farm, set up by Rwamatamu and gifted to a women’s cooperative. The setting was breathtaking and it was brilliant to see how the owners of Rwamatamu want to share their knowledge of efficient coffee production to help their neighbours be successful.

On our last day in Rwanda we visited a government-run dry mill. It was really impressive, full of machinery to sort coffee that arrives throughout the day from washing stations all over the country.

We flew to Burundi as the land border was closed. We stayed one night in Bujumbura then headed up to the mountains to stay at Migoti washing station. Migoti was founded by Dan and Pontien, both born in Burundi. Their vision is to help local farmers improve the quality of the coffee they grow, improve access to modern washing stations, and build opportunities to access the world market. While all the farms and facilities we visited were pretty remote, Migoti was a whole new adventure. We were each paired with a moto driver for some of the journey but also had a 15km hike uphill. We were accompanied along the way by groups of kids, some little more than toddlers, who clearly knew the area like the back of their hands.

At Migoti, we’d start the day with breakfast overlooking the valley and Lake Tanganyika then join the team working on various projects such as washing and sorting cherry, turning natural processed coffee by hand and removing mucilage by foot (imagine crushing grapes).

You visited a number of farms and washing stations on your trip. Can you describe how they worked?

Rwamatamu is a family farm that also operates a couple of washing stations. The coffee sold from Rwamatamu is a mixture of their own crops and lots from local smallholders. Rwamatamu adds a lot of value to their community because the amount smallholders grow is too small to sell to importers directly. Having a well-run washing station relatively close to their farm, means smallholders can deliver the day’s crop within the desired 8 hour window. Owners, Rutaganda Gaston and Mukantwaza Laetitia have built strong relationships with their neighbours by paying fairly and helping people to improve the quality and output of their land.

Migoti is a washing station. Local smallholders bring their crops here. By local, we’re still talking about people walking at least five kilometres, carrying their coffee cherry after a full day of picking. From what we saw, it was a really social event; everyone lined up chatting while waiting for their cherries to be sorted and weighed. Often kids tagged along to hang out with mum and dad. While farmers try their best to only pick ripe cherries, as they are paid less for unripe, there’s always the chance that some will end up in the bag. We found out that farmers have established their own floating stations where they can check for any unripe cherries (they float) before taking their day’s crop to Migoti.

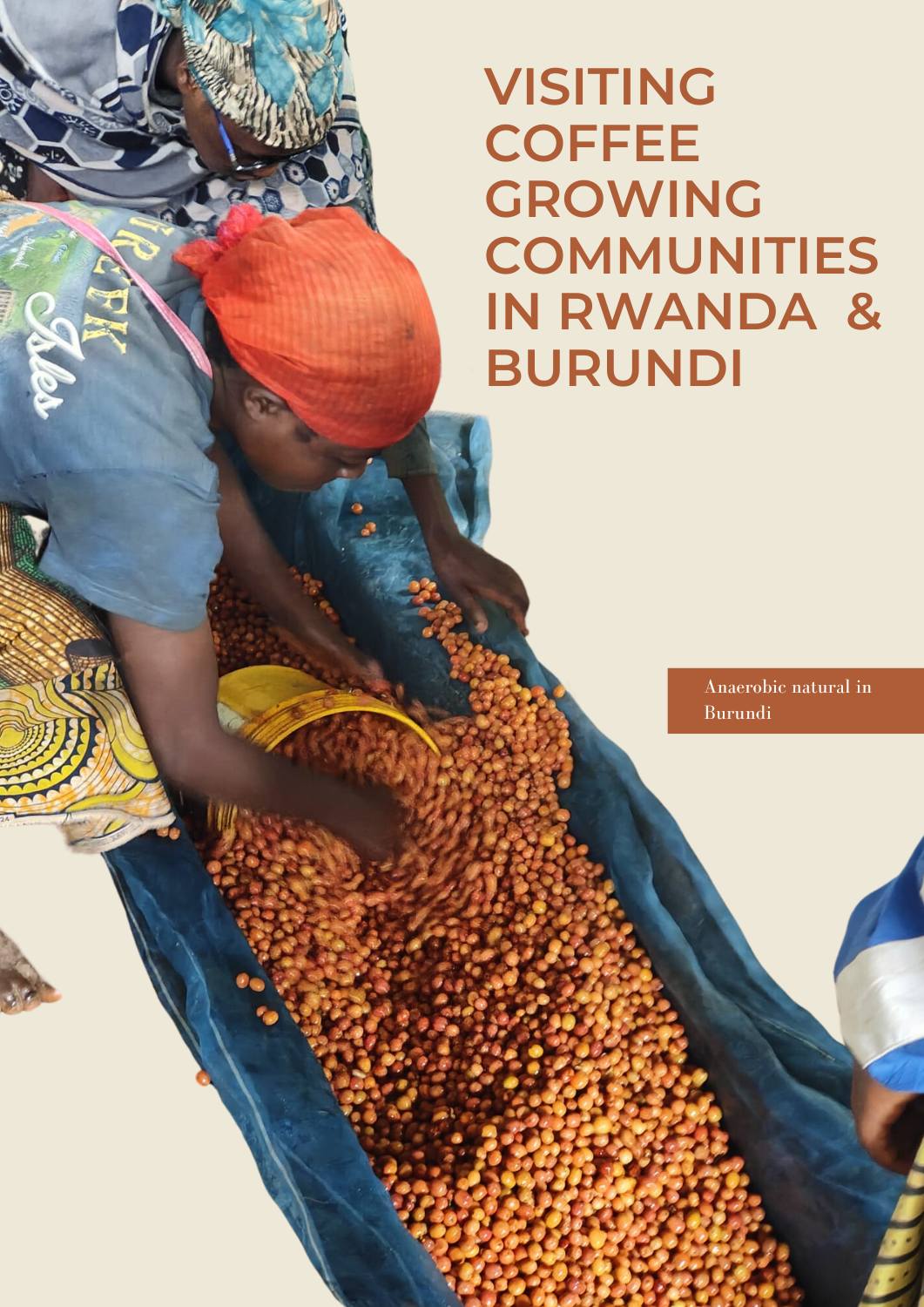

Dan and Pontien, who founded Migoti, have been working with farmers to improve the quality of coffee in the area. This includes investing time in different processing methods such as anaerobic. This is a version of natural processing where the whole cherries are placed in an airtight barrel, covered with water for 72 hours. Migoti, and the farmers they work with, are producing Burundian coffees of the highest quality in an effort to build a sustainable speciality coffee industry and create financial stability for the community.

Did you notice any major differences between the Rwandan farms/washing stations and those in Burundi?

Not really. They did things in similar ways, informed both by speciality coffee growing and processing conventions but also by the needs of the growers. In all the places we visited it was very clear that growers have to devote a huge amount of time to their work, particularly transporting, often on foot, the cherry that they've spent all day picking.

Has visiting the farms and washing stations changed how you think about the speciality coffee industry?

I didn’t fully appreciate the sheer amount of time and effort put into every coffee bean. The fact that smallholders can spend all day picking then have to carry their crop for five plus kilometers. It’s pretty mind blowing. There are also parts of the process in both coffee growing and in processing that cannot be rushed. It was lovely to experience a slower pace and see, in real time, the benefits of letting things take as long as needed.

How can roasters, cafes and coffee consumers as a whole support people involved in growing coffee?

Buying speciality grade coffee rather than commodity coffee is a great start. Unfortunately, much of what is found on supermarket shelves and in highstreet cafe chains will be lower quality and farmed on a huge scale. Issues such as deforestation, non-sustainable agricultural practices and forced labour are rife in the commodity coffee industry.

Coffee is graded for quality on a scale of 0 -100 with speciality grade being 80+. Having a look at a roaster’s website or chatting to staff at a roastery will hopefully give you a good indication of where their priorities lie. Speciality coffee is harder to cultivate than lower quality varieties, it’s grown at higher altitudes on smaller plots of land and it is easily affected by the changing climate. By choosing to buy speciality coffee, we’re offering stability to the farmers who grow it so they can weather the storms of an increasingly unpredictable climate, plant diseases and rising costs.